Floor Area Ratio in Relation to Commercial Real Estate Development

Floor area ratio (FAR) is a zoning metric that uses a building’s floor area and lot size to calculate the maximum square footage of a building that can be developed on a specific parcel of land. FAR is calculated by dividing the gross floor area (GFA) of a building by the total lot size. Higher floor area ratios mean that a potential development can be larger in terms of overall square feet. Different building types may have different maximum FARs based upon local zoning regulations.

How to Calculate Floor Area Ratio

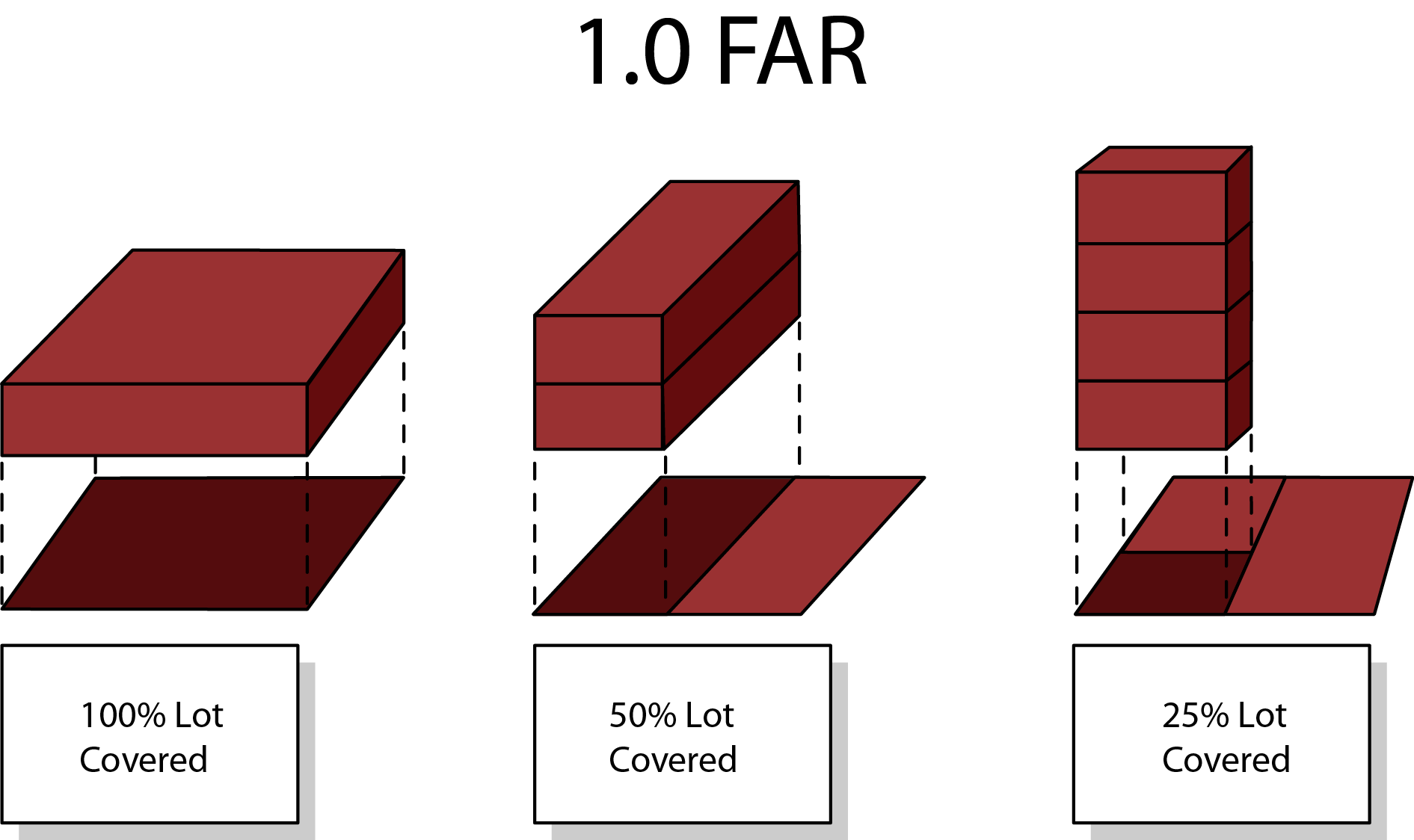

Floor area ratio examples for different building heights. Credit: DC Zoning Handbook

As previously mentioned, FAR is determined by dividing the total floor area of a building by the total lot size.

For example, a building with 20,000 square feet on a 5,000 square foot lot would have a FAR of 4.0 (20,000/5,000 = 4).

However, if you’re a developer, you will likely do this calculation in reverse, based on the maximum allowable FAR. This will allow you to determine the maximum building size, in square feet, that you can develop on a specific land parcel.

Let’s say the maximum FAR for a multifamily property in a certain area is 5.

If your total lot size is 10,000 square feet, you would multiply the total lot size by the floor area ratio to get the maximum square footage of 50,000 square feet.

Assuming there are no other zoning limitations (which there probably will be), that 50,000 square feet could be used to construct a 5-story building with 10,000 square feet per floor, a 10-story building with 5,000 square feet per floor, or a 20-story building with 2,500 square foot per floor, among a variety of other options that equal 50,000 square feet.

FAR’s Impact on Land Value

FAR has a major impact on land value, particularly in high-density urban areas, as lots with higher maximum floor area ratios allow developers to construct buildings with more leasable space, increasing potential profits.

For instance, a 10,000 square foot lot with a FAR of 7 would permit 40% more leasable space (70,000 max. square feet) than a lot with a FAR of 5 (50,000 max. square feet).

At a leasing price of $35 PSF (per square foot) per year, a building constructed on the first lot would be able to generate maximum leasing revenues of $2,450,000, while the second building would only be able to $1,750,000, a difference of $700,000 per year.

FAR is Generally Combined With Other Zoning Standards

In most cases, FAR is only one of several zoning regulations that developers will have to take into account, particularly when attempting to build a tall structure in an urban area. Other potential zoning regulations could involve maximum building height, and ingress/egress or lot coverage limitations, which will limit the maximum amount of square footage on the first floor of a building.

Another zoning limitation could be the parking ratio, which generally mandates that a building have a certain number of parking spots based on its square feet. The parking ratio of a building is typically denominated in the number of parking spaces per 1,000 square feet of building area. For example, an office building or retail development with 20,000 square feet and a parking ratio of 5 would need 100 parking spots (20,000/1,000 *5) to comply with parking ratio regulations.

Office buildings generally have a minimum parking ratio of 5, while industrial structures often have parking ratios of 2. To comply with ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) regulations, there also needs to be a certain number of handicapped parking spots. Currently, ADA regulations require one handicapped parking space for every 25 non-handicapped spaces. These spots mst be well labeled and sufficient in size to accommodate a typical van and wheelchair ramp.

If a building has an above-level, ground-level, or basement parking garage, rather than a separate ground-level parking lot, this will generally be excluded as square footage for the building’s FAR calculations and will not reduce the potential square footage for other uses. Other exclusions to FAR include unoccupied building areas like elevators shafts, equipment rooms, and stair towers.

How FAR is Determined by Zoning Officials and Urban Planners

FAR limits are determined by zoning and urban planning professionals and take into consideration a variety of factors. These include the number of potential residents for multifamily developments, the number of workers for an office building, as well as the estimated amount of traffic (in trips or mileage) that these people will take over a certain period of time.

In general, FAR and other zoning factors are designed to limit urban density and overcrowding to ensure a better quality of life for citizens living in a specific area. The potential strain of a building on local utility services, such as trash pickup and sewer usage, may also be factored in when determining maximum FAR for different building types in specific areas.

FAR Regulations, Conditional Use Permits, Variances, and Rezoning

If a developer’s building plans violate maximum FAR standards, they may sometimes be granted a variance or a conditional use permit (CUP) in order to adjust some of these restrictions. A conditional use permit provides a developer with a one-time exception to zoning regulations.

Similarly, a variance also allows developers an exception to zoning rules. To get approved for a variance, a developer generally needs to make a petition to the local zoning board and demonstrate that the regulation represents an “unnecessary hardship” to their development. They will also need to convince the zoning board that the variance does not negatively impact nearby residents.

In other cases, developers may petition a local government to rezone the area completely. This is typically more costly and time-consuming, as it often requires the support of the general public and may require a series of community meetings. Rezoning, unlike conditional use permits and variances, permanently changes local regulations.

In general, rezoning, conditional use permits, and variance requests are more likely to succeed if the development will likely create new jobs in the area or to serve an important need, such as creating more affordable housing.

In many cases, a developer will want to hire an experienced real estate zoning attorney or a zoning consultant to help them develop conditional use permit, variance, or zoning requests that conform to the requirements of the specific municipality in which their lot is located. This will generally speed up the process and increase the chance that their request will be granted.

An experienced attorney or consultant will not only be familiar with the exact zoning rules and regulations but will understand the prevailing attitudes of the zoning commission and already have significant relationships with zoning board members and others who play an important role in the zoning decision-making process.

FAR in Relation to Commercial Real Estate Finance

In many cases, real estate developers and investors will need to submit zoning reports to their lenders before getting approved for a commercial loan in order to prevent fines, lawsuits or other issues that could negatively impact a development project.

FAR compliance is one of the many factors that this zoning report will typically include. If the developer or investor’s plans violate FAR ratios, lot coverage limits, setback rules, building height limits, or other zoning regulations, they will need to provide proof that the project has been brought back into compliance via a variance, conditional use permit, or rezoning petition.

This is particularly important when borrowers attempt to get financing for new construction or significant rehabilitation of properties in high-density urban areas.

Before obtaining a commercial real estate loan to purchase, rehabilitate, or construct a commercial property, lenders will want to know that the borrower’s plans for the property do not interfere with any current zoning ordinances, and, if they do, that the issue has already been handled via a CUP, variance, or a full rezoning of the area in question.